Dea Drug Schedule List

- Jan 30, 2015 - DEA Controlled Substances: The federal Controlled Substances Act, enacted in 1970, lists approximately 200 drugs or chemicals that have the.

- DEA Drug Code Number: DEA Number: CSA Schedule: List Number: Illicit Uses and Threshold Quantities. A controlled substance analogue is a substance which is intended for human consumption, is structurally substantially similar to a schedule I or schedule II substance, is pharmacologically substantially similar to a schedule I or schedule II.

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has announced its decision: It will keep marijuana in the same legal, regulatory category as heroin — schedule 1. To many people, this is outrageous.

The removal of cannabis from Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, the most tightly restricted category reserved for drugs that have 'no currently accepted medical use,' has been proposed repeatedly since 1972.

Rescheduling proponents argue that cannabis does not meet the Controlled Substances Act's strict criteria for placement in Schedule I and so the government is required by law to permit medical use or to remove the drug from federal control altogether. The US government, on the other hand, maintains that cannabis is dangerous enough to merit Schedule I status. The dispute is based on differing views on both how the Act should be interpreted and what kinds of scientific evidence are most relevant to the rescheduling decision.

The Act provides a process for rescheduling controlled substances by petitioning the Drug Enforcement Administration. The first petition under this process was filed in 1972 to allow cannabis to be legally prescribed by physicians. The petition was ultimately denied after 22 years of court challenges, but a synthetic pill form of cannabis's psychoactive ingredient, THC, was rescheduled in 1986 to allow prescription under schedule II.[1] In 1999, it was again rescheduled to allow prescription under schedule III.

A second petition, based on claims related to clinical studies, was denied in 2001. The most recent rescheduling petition filed by medical cannabis advocates was in 2002, but it was denied by the DEA in July 2011. Subsequently, medical cannabis advocacy group Americans for Safe Access filed an appeal, Americans for Safe Access v. Drug Enforcement Administration in January 2012 with the District of Columbia Circuit, which was heard on 16 October 2012[2] and denied on 22 January 2013.[3]

As of August 2018, 30 states and Washington, D.C. have legalized the use of medical marijuana.[4] At a congressional hearing in June 2014, the Deputy Director for Regulatory Programs at the FDA said the agency was conducting an analysis on whether marijuana should be downgraded, at the request of the DEA.[5] In August 2016 the DEA reaffirmed its position and refused to remove Schedule I classification.[6] However, the DEA announced that it will end restrictions on the supply of marijuana to researchers and drug companies that had previously only been available from the government's own facility at the University of Mississippi.[7]

Advocates of marijuana legalization argue that the budgetary impact of removing cannabis from Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act and legalizing its use in the United States could save billions by reducing government spending for prohibition enforcement in the criminal justice system. Additionally, they argue that billions in annual tax revenues could be generated through proposed taxation and regulation.[8] Patient advocates argue that by reclassifying marijuana, millions of Americans who are currently prevented from using medical marijuana would be able to benefit from its therapeutic value.[citation needed].

- 2Arguments for and against

- 3Process

- 4History

- 5State level reclassification

Background[edit]

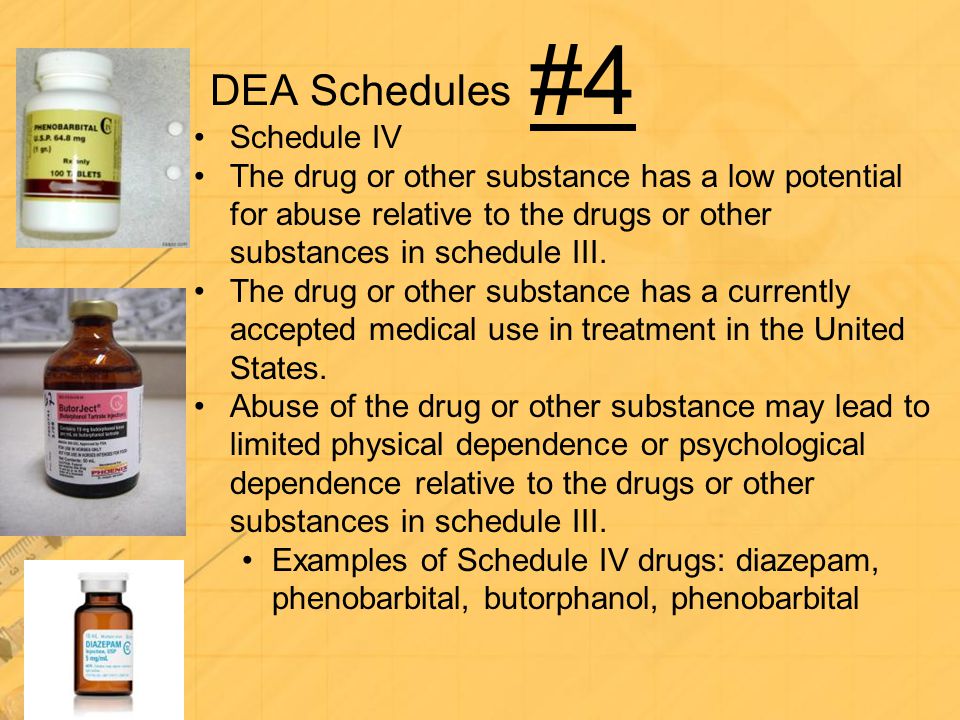

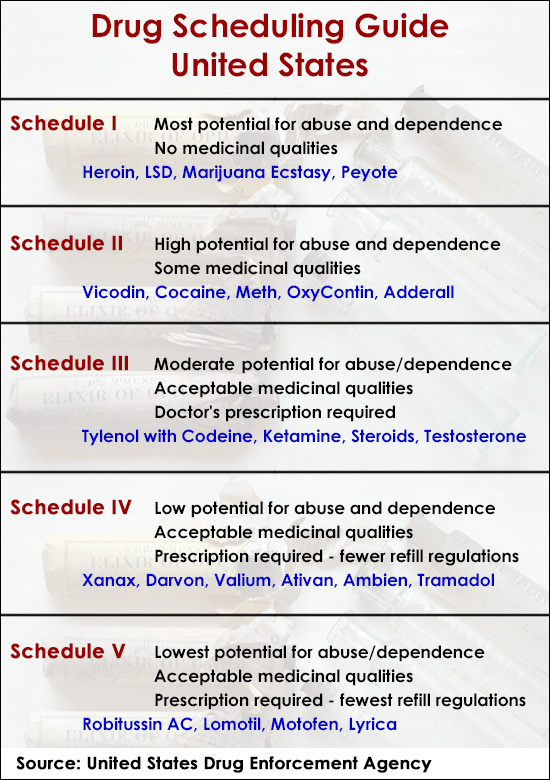

| Schedules of Controlled Substances |

|---|

| Schedule I |

|

| Schedule II |

|

| Schedule III |

|

| Schedule IV |

|

| Schedule V |

Schedule I is the only category of controlled substances not allowed to be prescribed by a physician. Under 21 U.S.C.§ 812, drugs must meet three criteria in order to be placed in Schedule I:

- The drug or other substance has a high potential for abuse.

- The drug or other substance has no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States.

- There is a lack of accepted safety for use of the drug or other substance under medical supervision.

In 1970, Congress placed cannabis into Schedule I on the advice of Assistant Secretary of HealthRoger O. Egeberg. His letter to Harley O. Staggers, Chairman of the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, indicates that the classification was intended to be provisional:

Dear Mr. Chairman: In a prior communication, comments requested by your committee on the scientific aspects of the drug classification scheme incorporated in H.R. 18583 were provided. This communication is concerned with the proposed classification of marijuana.

It is presently classed in schedule I(C) along with its active constituents, the tetrahydrocannibinols and other psychotropic drugs.

Some question has been raised whether the use of the plant itself produces 'severe psychological or physical dependence' as required by a schedule I or even schedule II criterion. Since there is still a considerable void in our knowledge of the plant and effects of the active drug contained in it, our recommendation is that marijuana be retained within schedule I at least until the completion of certain studies now underway to resolve the issue.[9]

In 1972, the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse released a report favoring decriminalization of cannabis. The Nixon administration took no action to implement the recommendation, however.

Arguments for and against[edit]

For rescheduling[edit]

Jon Gettman, former director of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, has argued that cannabis does not fit each of the three statutory criteria for Schedule I. Gettman believes that 'high potential for abuse' means that a drug has a potential for abuse similar to that of heroin or cocaine.[10] Gettman argues further that since laboratory animals do not self-administer cannabis, and because cannabis' toxicity is virtually non-existent compared to that of heroin or cocaine, cannabis lacks the high abuse potential required for inclusion in Schedule I or II.[citation needed]

Gettman also states: 'The acceptance of cannabis' medical use by eight (now twenty-five and DC) states since 1996 and the experiences of patients, doctors, and state officials in these states establish marijuana's accepted medical use in the United States.'[11] Specifically, Alaska, Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Washington, Washington DC, and Wisconsin, have enacted legislation allowing the medical use of cannabis by their citizens.[12] A minimum of 142,798 patients are currently using medical cannabis legally in these states, and over 2,500 different physicians have recommended it for use by their patients.[13]

In his petition, Gettman also argues that cannabis is an acceptably safe medication. He notes that a 1999 Institute of Medicine report found that 'except for the harms associated with smoking, the adverse effects of marijuana use are within the range of effects tolerated for other medications.' He points out that there are a number of delivery routes that were not considered by the Institute, such as transdermal, sublingual, and even rectal administration, in addition to vaporizers, which release cannabis' active ingredients into the air without burning the plant matter.[14]

A study published in the March 1, 1990 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences stated that 'there are virtually no reports of fatal cannabis overdose in humans' and attributed this safety to the low density of cannabinoid receptors in areas of the brain controlling breathing and the heart.[15][16] Gettman claims that the discovery of the cannabinoid receptor system in the late 1980s revolutionized scientific understanding of cannabis' effects and provided further evidence that it does not belong in Schedule I.

In 2003, the United States government patented cannabinoids, including those in marijuana that cause users to get 'high' (such as THC) based on these chemicals' prevention of trauma- and age-related brain damage.[17]

In January 2008, the American College of Physicians called for a review of cannabis's Schedule I classification in its position paper titled 'Supporting Research into the Therapeutic Role of Marijuana' It stated therein: 'Position 4: ACP urges an evidence-based review of marijuana's status as a Schedule I controlled substance to determine whether it should be reclassified to a different schedule. This review should consider the scientific findings regarding marijuana's safety and efficacy in some clinical conditions as well as evidence on the health risks associated with marijuana consumption, particularly in its crude smoked form.' [18]

From 2008 to 2012, the American Patients Rights Association, in cooperation with Medical Marijuana expert Kim Quiggle, lobbied the federal government over what is now known as the 'Mary Lou Eimer Criteria' based on a medical study performed by Quiggle on over 10,000 chronically ill and terminally ill patients use of medical marijuana in Southern California. This study provided conclusive evidence that medical marijuana provided a safer and alternative application to many current pharmaceutical products available for patients, especially those with cancer and HIV/AIDS. The 'Mary Lou Eimer Criteria' was instrumental in the issuance of the Cole Memorandum which has set federal guidelines over states with medical marijuana laws; and has urged the federal government to reschedule marijuana to a Class IV or Class V controlled substance based on the results of the Quiggle Study.

Since 2012, The American Patients Rights Association (APRA), based in Los Angeles, has become the strongest advocate for rescheduling medical marijuana to a Schedule V pharmaceutical. APRA's Regulatory Affairs Director, Patrick Rohde, has been highly critical of Colorado's legalization of marijuana, stating that the state government '..has violated patient's rights through its recreational marijuana regulatory scheme' labeling the program 'Tax & Jail' in reference to the state's drugged driving laws and high taxes on medical marijuana.

'Regulations regarding 'driving under the influence of 3 micrograms of THC or greater' is pseudoscience and an abuse of regulatory oversight; I could have 3 micrograms of THC in my blood stream from medical marijuana that I medicated with over a month ago. I could have 3 micrograms in my blood even by simply inhaling too much second hand..APRA wishes to see such decisions on public health reserved for physicians and laboratories with professional expertise.' - Patrick Rohde [19]

Against rescheduling[edit]

In 1992, DEA Administrator Robert Bonner promulgated five criteria, based somewhat on the Controlled Substances Act's legislative history, for determining whether a drug has an accepted medical use.[20] The DEA claims that cannabis has no accepted medical use because it does not meet all of these criteria:[21]

- The drug's chemistry is known and reproducible;

- There are adequate safety studies;

- There are adequate and well-controlled studies proving efficacy;

- The drug is accepted by qualified experts; and

- The scientific evidence is widely available.

These criteria are not binding; they were created by DEA and may be altered at any time. Judicial deference to agency decisions is what has kept them in effect, despite the difference between these and the statutory criteria. Cannabis is one of several plants with unproven abuse potential and toxicity that Congress placed in Schedule I. The DEA interprets the Controlled Substances Act to mean that if a drug with even a low potential for abuse — say, equivalent to a Schedule V drug — has no accepted medical use, then it must remain in Schedule I:[21]

When it comes to a drug that is currently listed in Schedule I, if it is undisputed that such drug has no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States and a lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision, and it is further undisputed that the drug has at least some potential for abuse sufficient to warrant control under the CSA, the drug must remain in schedule I. In such circumstances, placement of the drug in schedules II through V would conflict with the CSA since such drug would not meet the criterion of 'a currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States.' 21 USC 812(b).Therefore, even if one were to assume, theoretically, that your assertions about marijuana's potential for abuse were correct (i.e., that marijuana had some potential for abuse but less than the 'high potential for abuse' commensurate with schedules I and II), marijuana would not meet the criteria for placement in schedules III through V since it has no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States—a determination that is reaffirmed by HHS in the attached medical and scientific evaluation.

This argument silently rejects the concept that if a drug does not meet the criteria for any schedule, it should not be in any schedule.

The Department of Health and Human Services rejects the argument that laboratory animals' failure to self-administer cannabis is conclusive proof of its low potential for abuse:[21]

The Secretary disagrees with Mr. Gettman's assertion that '[t]he accepted contemporary legal convention for evaluating the abuse potential of a drug or substance is the relative degree of self-administration the drug induces in animal subjects.' As discussed above, self-administration tests that identify whether a substance is reinforcing in animals are but one component of the scientific assessment of the abuse potential of a substance. Positive indicators of human abuse liability for a particular substance, whether from laboratory studies or epidemiological data, are given greater weight than animal studies suggesting the same compound has no abuse potential.

The Food and Drug Administration elaborates on this, arguing that the widespread use of cannabis, and the existence of some heavy users, is evidence of its 'high potential for abuse,' despite the drug's lack of physiological addictiveness:[21]

[P]hysical dependence and toxicity are not the only factors to consider in determining a substance's abuse potential. The large number of individuals using marijuana on a regular basis and the vast amount of marijuana that is available for illicit use are indicative of widespread use. In addition, there is evidence that marijuana use can result in psychological dependence in a certain proportion of the population.

The Department of Justice also considers the fact that people are willing to risk scholastic, career, and legal problems to use cannabis to be evidence of its high potential for abuse:[21]

Throughout his petition, Mr. Gettman argues that while many people 'use' cannabis, few 'abuse' it. He appears to equate abuse with the level of physical dependence and toxicity resulting from cannabis use. Thus, he appears to be arguing that a substance that causes only low levels of physical dependence and toxicity must be considered to have a low potential for abuse. The Secretary does not agree with this argument. Physical dependence and toxicity are not the only factors that are considered in determining a substance's abuse potential. The actual use and frequency of use of a substance, especially when that use may result in harmful consequences such as failure to fulfill major obligations at work or school, physical risk-taking, or even substance-related legal problems, are indicative of a substance's abuse potential. The same and much worse can also be said about the clear abuse of alcohol by many Americans.

Process[edit]

Cannabis could be rescheduled either legislatively, through Congress, or through the executive branch. Congress has so far rejected all bills to reschedule cannabis. However, it is not unheard of for Congress to intervene in the drug scheduling process; in February 2000, for instance, the 105th Congress, in its second official session, passed Public Law 106-172, also known as the Hillory J. Farias and Samantha Reed Date-Rape Drug Prohibition Act of 2000,[22] adding GHB to Schedule I.[23] On June 23, 2011, Rep. Barney Frank and Rep. Ron Paul introduced H.R. 2306,[24] legislation that would completely remove cannabis from the federal schedules, limiting the federal government's role to policing cross-border or interstate transfers into states where it remains illegal.

The Controlled Substances Act also provides for a rulemaking process by which the United States Attorney General can reschedule cannabis administratively. These proceedings represent the only means of legalizing medical cannabis without an act of Congress. Rescheduling supporters have often cited the lengthy petition review process as a reason why cannabis is still illegal.[10] The first petition took 22 years to review, the second took 7 years, the third was denied 9 years later. A 2013 petition by two state governors is still pending.

Rulemaking proceedings[edit]

| Stages in rescheduling proceedings |

|---|

|

The United States Code, under Section 811 of Title 21,[25] sets out a process by which cannabis could be administratively transferred to a less-restrictive category or removed from Controlled Substances Act regulation altogether. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) evaluates petitions to reschedule cannabis. However, the Controlled Substances Act gives the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), as successor agency of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, great power over rescheduling decisions.

After the DEA accepts the filing of a petition, the agency must request from the HHS Secretary 'a scientific and medical evaluation, and his recommendations, as to whether such drug or other substance should be so controlled or removed as a controlled substance.' The Secretary's findings on scientific and medical issues are binding on the DEA.[26] The HHS Secretary can even unilaterally legalize cannabis: '[I]f the Secretary recommends that a drug or other substance not be controlled, the Attorney General shall not control the drug or other substance.' 21 U.S.C.§ 811(b).

Factors[edit]

Unless an international treaty requires controlling a substance, the Attorney General must, in finding whether the drug meets the three criteria for placement in a particular schedule, consider the following factors:[citation needed]

- The drug's actual or relative potential for abuse.

- Scientific evidence of its pharmacological effect, if known.

- The state of current scientific knowledge regarding the drug or other substance.

- Its history and current pattern of abuse.

- The scope, duration, and significance of abuse.

- What, if any, risk there is to the public health.

- Its psychological or physiological dependence liability.

- Whether the substance is an immediate precursor of a controlled substance.

International treaty[edit]

If an international treaty, ratified by the U.S., mandates that a drug be controlled, the Attorney General is required to 'issue an order controlling such drug under the schedule he deems most appropriate to carry out such obligations' without regard to scientific or medical findings.[27] Under the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, cannabis and cannabis resin are classified, at the insistence of the United States,[28] under Schedule IV, that treaty's most strictly controlled category of drugs.[29] However, Article 4(c) of the Single Convention specifically excludes medicinal drug use from prohibition, requiring only that Parties 'limit exclusively to medical and scientific purposes the production, manufacture, export, import, distribution of, trade in, use and possession of drugs'.[29] On the other hand, Article 2(5)(b) states that for Schedule IV drugs:

- A Party shall, if in its opinion the prevailing conditions in its country render it the most appropriate means of protecting the public health and welfare, prohibit the production, manufacture, export and import of, trade in, possession or use of any such drug except for amounts which may be necessary for medical and scientific research only, including clinical trials therewith to be conducted under or subject to the direct supervision and control of the Party.[30]

The clause '..in its opinion..' refers to a judgment that each nation makes for itself. The official Commentary on the treaty indicates that Parties are required to make the judgment in good faith. Thus, if in the opinion of the United States, limiting cannabis use solely to research purposes would be 'the most appropriate means of protecting the public health and welfare,' the U.S. would be required to do that. Presumably, this would greatly restrict the possibilities for medical use.

Jon Gettman, in Science and the End of Marijuana Prohibition, claims that 'if prohibition ends in the U.S. it must also end world-wide because U.S. law requires that we amend international drug control treaties to correspond with our own findings on scientific and medical issues'.[10] This is at least partially correct; 21 U.S.C. § 811(d)(2)(B) of the Controlled Substances Act states that if the United NationsCommission on Narcotic Drugs proposes rescheduling a drug, the HHS Secretary 'shall evaluate the proposal and furnish a recommendation to the Secretary of State which shall be binding on the representative of the United States in discussions and negotiations relating to the proposal'.[25] As the major financial contributor to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and related agencies, the U.S. has a great deal of influence over international drug policy.[31] However, former United Nations Drug Control Programme Chief of Demand Reduction Cindy Fazey points out in The UN Drug Policies and the Prospect for Change that since cannabis restrictions are embedded in the text of the Single Convention,[30] complete legalization would require denunciation of the Single Convention,[32] amendment of the treaty,[33] or a reinterpretation of its provisions that would likely be opposed by the International Narcotics Control Board.[34]

History[edit]

1972 petition[edit]

In 1972 the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) petitioned the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD) (now the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)) to transfer cannabis to Schedule II so that it could be legally prescribed by physicians. The BNDD declined to initiate proceedings on the basis of their interpretation of U.S. treaty commitments.

In 1974, the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled against the government and ordered them to process the petition (NORML v. Ingersoll 497 F.2d 654). The government continued to rely on treaty commitments in their interpretation of scheduling-related issues concerning the NORML petition. In 1977, the Court issued a decision clarifying that the Controlled Substances Act requires a full scientific and medical evaluation and the fulfillment of the rescheduling process before treaty commitments can be evaluated (NORML v. DEA 559 F.2d 735). On October 16, 1980, the Court ordered the government to start the scientific and medical evaluations required by the NORML petition (NORML v. DEA Unpublished Disposition, U.S. App. LEXIS 13100).

Meanwhile, some members of Congress were taking action to reschedule the drug legislatively. In 1981, the late Rep. Stuart McKinney introduced a bill to transfer cannabis to Schedule II.[35] It was co-sponsored by a bipartisan coalition of 84 House members, including prominent RepublicansNewt Gingrich (GA), Bill McCollum (FL), John Porter (IL), and Frank Wolf (VA).[36] After the bill died in committee, Rep. Barney Frank began annually introducing nearly identical legislation.[37] All of Frank's bills have suffered the same fate, though, without attracting more than a handful of co-sponsors.

On October 18, 1985, the DEA issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking to transfer 'Synthetic Dronabinol in Sesame Oil and Encapsulated in Soft Gelatin Capsules' — a pill form of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, the main psychoactive component of cannabis, sold under the brand name Marinol — from Schedule I to Schedule II (DEA 50 FR 42186-87). The government issued its final rule rescheduling the drug on July 13, 1986 (DEA 51 FR 17476-78). The disparate treatment of cannabis and the expensive, patentable Marinol prompted reformers to question the DEA's consistency.[38][39]

| 1986 Hearings |

|---|

| Parties supporting rescheduling |

|

| Parties opposing rescheduling |

|

In the summer of 1986, the DEA administrator initiated public hearings on cannabis rescheduling. The hearings lasted two years, involving many witnesses and thousands of pages of documentation. On September 6, 1988, DEA Chief Administrative Law Judge Francis L. Young ruled that cannabis did not meet the legal criteria of a Schedule I prohibited drug and should be reclassified. He declared that cannabis in its natural form is 'one of the safest therapeutically active substances known to man. (T)he provisions of the (Controlled Substances) Act permit and require the transfer of marijuana from Schedule I to Schedule II'.[40]

Then-DEA Administrator John Lawn overruled Young's determination. Lawn said he decided against rescheduling cannabis based on testimony and comments from numerous medical doctors who had conducted detailed research and were widely considered experts in their respective fields. Later Administrators agreed. 'Those who insist that marijuana has medical uses would serve society better by promoting or sponsoring more legitimate research,' former DEA Administrator Robert Bonner opined in 1992. This statement was quoted by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) in its membership drives.[41]

In 1994, the D.C. Court of Appeals finally affirmed the DEA Administrator's power to overrule Judge Young's decision (Alliance for Cannabis Therapeutics v. DEA. 15 F.3d 1131). The petition was officially dead. 'Each of the doctors testifying on behalf of NORML claimed that his opinion was based on scientific studies, yet with one exception, none could identify, under oath, the scientific studies they relied on,' DEA Administrator Thomas A. Constantine remarked in 1995.[42]

1995 petition[edit]

On July 10, 1995, Jon Gettman and High Times Magazine filed another rescheduling petition with the DEA. This time, instead of focusing on cannabis' medical uses, the petitioners claimed that cannabis did not have the 'high potential for abuse' required for Schedule I or Schedule II status. They based their claims on studies of the brain's cannabinoid receptor system conducted by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) between 1988 and 1994. In particular, they claim that a 1992 study by M. Herkenham et al.,[43] 'using a lesion-technique, established that there are no cannabinoid receptors in the dopamine-producing areas of the brain'.[16] Other studies, summarized in Gettman's 1997 report Dopamine and the Dependence Liability of Marijuana, showed that cannabis has only an indirect effect on dopamine transmission.[16] This suggested that cannabis' psychoactive effects are produced by a different mechanism than addictive drugs such as amphetamine, cocaine, ethanol, nicotine, and opiates. The National Institute on Drug Abuse, however, continued to publish literature denying this finding. For instance, NIDA claims the following in its youth publication The Science Behind Drug Abuse:[44]

- A chemical in marijuana, THC, triggers brain cells to release the chemical dopamine. Dopamine creates good feelings — for a short time. Here's the thing: Once dopamine starts flowing, a user feels the urge to smoke marijuana again, and then again, and then again. Repeated use could lead to addiction, and addiction is a brain disease.

In January 1997, the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) asked the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to conduct a review of the scientific evidence to assess the potential health benefits and risks of cannabis and its constituent cannabinoids.[45] In 1999, the IOM recommended that medical cannabis use be allowed for certain patients in the short term, and that preparations of isolated cannabinoids be developed as a safer alternative to smoked cannabis. The IOM also found that the gateway drug theory was 'beyond the issues normally considered for medical uses of drugs and should not be a factor in evaluating the therapeutic potential of marijuana or cannabinoids.'

Both sides claimed that the IOM report supported their position. The DEA publication Exposing the Myth of Smoked Medical Marijuana interpreted the IOM's statement, 'While we see a future in the development of chemically defined cannabinoid drugs, we see little future in smoked marijuana as a medicine,' as meaning that smoking cannabis is not recommended for the treatment of any disease condition.[46] Cannabis advocates pointed out that the IOM did not study vaporizers, devices which, by heating cannabis to 185 °C, release therapeutic cannabinoids while reducing or eliminating ingestion of various carcinogens.[47]

On July 2, 1999, Marinol was again rescheduled, this time from Schedule II to the even less-restrictive Schedule III, while cannabis remained in Schedule I (64 FR 35928).[48] The petitioners argued that the distinction between the two drugs was arbitrary, and that cannabis should be rescheduled as well. The DEA, however, continued to support Marinol as a method of THC ingestion without harmful smoke inhalation.

The DEA published a final denial of Gettman's petition on April 18, 2001.[49] The U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit upheld the agency's decision on May 24, 2002, ruling that the petitioners were not sufficiently injured to have standing to challenge DEA's determinations in federal court (290 F.3d 430).[50] Since the appeal was dismissed on a technicality, it is unknown what position the Court would have taken on the merits of the case.

2002 petition[edit]

On October 9, 2002, the Coalition for Rescheduling Cannabis filed another petition.[51] The new organization consisted of medical cannabis patients and other petitioners who would be more directly affected by the DEA's decision. On April 3, 2003, the DEA accepted the filing of that petition. According to Jon Gettman, 'In accepting the petition the DEA has acknowledged that the Coalition has established a legally significant argument in support of the recognition of the accepted medical use of cannabis in the United States.'

In a footnote to the majority decision in Gonzales v. Raich, Justice John Paul Stevens said that if the scientific evidence offered by medical cannabis supporters is true, it would 'cast serious doubt' on the Schedule I classification.[52]

On May 23, 2011, the Coalition for Rescheduling Cannabis filed suit in the District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals to compel the DEA to formally respond to its 2002 petition to have marijuana rescheduled under the provisions of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA). The writ of mandamus filed alleged that the lack of decision by DEA, 'presents a paradigmatic example of unreasonable delay under Telecommunications Research & Action Ctr. v. FCC.'[53] In response to the suit, the DEA issued a Final Determination on the Petition for Rescheduling on July 8, 2011.[54][55] The Petition for Writ of Mandamus was subsequently dismissed by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals as moot on October 14, 2011.[56]

In response to the petition's denial, medical cannabis advocacy group Americans for Safe Access appealed to the D.C. Circuit on January 23, 2012.[57] Oral arguments in the case Americans for Safe Access v. DEA were heard on October 16, 2012.[58] On the same day the case was heard, the court ordered the plaintiffs (ASA) to clarify their arguments on standing.[59] In response, ASA filed a supplemental brief on October 22, 2012, detailing how plaintiff Michael Krawitz was harmed by the federal government's policy on medical marijuana due to being denied treatment by the Department of Veterans Affairs.[60] A ruling that acknowledged Krawitz's standing, but ultimately stood by the DEA was made on January 22, 2013.United States Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit (January 22, 2013). 'AMERICANS FOR SAFE ACCESS, ET AL., Petitioners, v. DRUG ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION, Respondent, CARL ERIC OLSEN, Intervenor'.

2009 petition[edit]

On December 17, 2009, Rev. Bryan A. Krumm, CNP, filed a rescheduling petition for Cannabis with the DEA arguing that 'because marijuana does not have the abuse potential for placement in Schedule I of the CSA, and because marijuana now has accepted medical use in 13 states, and because the DEA's own Administrative Law Judge has already determined that marijuana is safe for use under medical supervision, the federal definition for a schedule I controlled substance, 21 U.S.C. § 812(b)(1)(A)-(C), no longer applies to marijuana and federal law must be amended to reflect these changes.' Krumm demanded an expedited ruling in order to protect his health and welfare, as well as that of all citizens of United States who may benefit from this safe and effective medication.

Rev. Krumm did not request that cannabis be moved to any specific schedule of control under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) and has reserved his right to challenge any incorrect findings by the FDA and/or DEA whether Cannabis should even be regulated under the CSA.

2011 petition[edit]

On November 30, 2011, Washington State Governor Christine Gregoire announced the filing of a petition[61][62] with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration asking the agency to reclassify marijuana as a Schedule 2 drug, which will allow its use for treatment – prescribed by doctors and filled by pharmacists. Gov. Lincoln Chafee (I-Rhode Island) also signed the petition.

On December 23, 2015, Tom Angell reported that the FDA had finally issued a recommendation to the DEA regarding both the 2009 and 2011 petitions.[63] Requests have been made to both the DEA and FDA under the Freedom of Information Act to determine the details of that recommendation.

2011 bill[edit]

On June 23, 2011, Rep. Barney Frank (D-MA), along with 1 Republican and 19 Democratic cosponsors, introduced the Ending Federal Marijuana Prohibition Act of 2011, which would have removed marijuana and THC from the list of Schedule I controlled substances and would have provided that the Controlled Substances Act not apply to marijuana except when transported to a jurisdiction where its use is illegal.[64] The bill was referred to committee but died when no further action was taken.[64]

2012 bill[edit]

On November 27, 2012, after voters in the states of CO and WA voted to legalize recreational use of marijuana, Rep. Diana DeGette (D-CO) introduced a bill referred to as the 'Respect States and Citizens Rights Act' which aimed to amend the Controlled Substances Act to exclude any state that has legalized marijuana (for medical OR recreational use) from marijuana provisions of the CSA, effectively giving state law precedence over federal law in cases where an individual (or commercial enterprise) is acting within the letter of state law regarding marijuana/cannabis.[65] The bill was referred to committee but died when no further action was taken.[65] The same bill was reintroduced later in the 113th and 114th Congresses, where it died each time.[66]

2015 bill[edit]

On February 20, 2015, Rep. Jared Polis (D-CO), along with 1 Republican and 18 Democratic cosponsors, introduced the Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol Act, which would have, among other provisions, directed the Attorney General to remove marijuana from all schedules of controlled substances under the Controlled Substances Act; prohibited transport of marijuana into a jurisdiction in which its possession, use, or sale is prohibited; and granted the Food and Drug Administration the same authorities with respect to marijuana as it has for alcohol.[67] The bill was referred to committee but died when no further action was taken.[67]

2016[edit]

In August 2016, the DEA rejected calls to reschedule marijuana, but indicated an increase in availability for research.[68]

The 2016 platform of the Democratic Party called for removal of marijuana from Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, 'providing a reasoned pathway for future legalization' of marijuana.[69] This language was approved in a close vote (81-80 vote) in the platform committee.[70]

List Of Common Controlled Substances 2018

2017[edit]

In February 2017, Morgan Griffith, a Virginia Republican, introduced H.R. 714, Legitimate Use of Medicinal Marijuana Act, that would move cannabis to Schedule II.[71] Griffith had introduced a bill under the same name in 2014.[72]

In April 2017, Matt Gaetz, a Florida Republican, cosponsored House Resolution 2020 to move cannabis to Schedule III.[73][74]

In May 2017, following a resolution adopted at the 2016 annual convention to support cannabis to treat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the American Legion petitioned the White House for a meeting to discuss rescheduling or descheduling cannabis and allowing it to be used medically.[75][76][77]

In July 2017, a lawsuit was brought in U.S. District Court against the heads of the DEA and Justice Department on the grounds that Schedule I listing of cannabis is 'so irrational that it violates the U.S. Constitution'.[78] This lawsuit was dismissed by Judge Alvin K. Hellerstein who ruled that that the DEA has authority and before bringing the lawsuit the plaintiffs were required to exhaust administrative remedies including petitioning the DEA to reschedule cannabis.[79]

2018[edit]

The 2018 United States farm bill descheduled some cannabis products from the Controlled Substances Act for the first time.[80][81][82]

Schedule 1 Through 5 Drugs

State level reclassification[edit]

Legality of cannabis in the United States Notes:

Notes:· Includes laws which have not yet gone into effect.

· Cannabis remains a Schedule I drug under federal law.

· Some Indian reservations have legalization policies separate from the states they are located in.

· Cannabis is illegal in all federal enclaves.

In addition to the federal government's classification, each state maintains a similar classification list and it is possible for these lists to conflict.

California[edit]

Proposition 215, the Compassionate Use Act, is a voter initiative, passed in 1996, that made California the first state to legalize cannabis for medical use. California Senate Bill 420, the Medical Marijuana Program Act, was passed in 2004 with the following purpose: '(1) Clarify the scope of the application of the act and facilitate the prompt identification of qualified patients and their designated primary caregivers in order to avoid unnecessary arrest and prosecution of these individuals and provide needed guidance to law enforcement officers. (2) Promote uniform and consistent application of the act among the counties within the state. (3) Enhance the access of patients and caregivers to medical marijuana through collective, cooperative cultivation projects.'

In 2016, the Adult Use of Marijuana Act was voted into law, legalizing recreational consumption for those over 21 in the state.

Colorado[edit]

On Nov. 6, 2012: After passing Amendment 64, Colorado became one of the first two states to legalize the recreational use of marijuana for individuals over the age of 21.[83]

Florida[edit]

On January 27, 2014, the Florida Supreme Court approved the ballot language for a proposed constitutional amendment allowing the medical use of marijuana, following a successful petition drive.[84] The amendment proposal appeared on Florida's November 2014 general election ballot and received 58% of the vote, below the 60% requirement for adoption. The campaign was notable for opposition funding by casino magnate and Republican Party donor Sheldon Adelson.[85] United for Care, the pro-medical cannabis organization responsible for the initial petition, wrote an updated version for the 2016 general election.[86] The Florida Medical Marijuana Legalization Initiative, also known as Amendment 2, was on the November 8, 2016, ballot in Florida as an initiated constitutional amendment. The amendment was approved by 71.32% of the vote making it the highest percentage win in 2016 of any other state cannabis ballot in the United States.[87]

Iowa[edit]

On Feb. 17, 2010, after reviewing testimony from four public hearings and reading through more than 10,000 pages of submitted material, members of the Iowa Board of Pharmacy unanimously voted to recommend that the Iowa legislature remove marijuana from Schedule I of the Iowa Controlled Substances Act.[88]

Minnesota[edit]

On March 16, 2011, Kurtis W. Hanna and Ed Engelmann petitioned the Minnesota Board of Pharmacy to initiate rule making to remove Cannabis from the list of Schedule I substance in Minnesota's version of the Uniform Controlled Substances Act.[89][90] The Board was informed when they denied the petition at their meeting on May 11, 2011 by Kurtis Hanna that he planned on filing for judicial review of the agency's decision. In response, the Board voted to petition the State Legislature to remove the Board's authority to remove substances from Schedule I. At a Conference Committee for Omnibus Drug Bill HF57 on May 18, 2011, the following sentence was added to the bill, 'The Board of Pharmacy may not delete or reschedule a drug that is in Schedule I' and the following sentence of statute was deleted, 'the state Board of Pharmacy [..] shall annually, on or before May 1 of each year, conduct a review of the placement of controlled substances in the various schedules.'[91] The bill was signed into law by Governor Dayton on May 24, 2011.[92] Kurtis Hanna never filed a lawsuit against the Board of Pharmacy due to the belief that it would be moot.

Oregon[edit]

Chakravakam telugu serial full episodes. In June 2010, the Oregon Board of Pharmacy reclassified marijuana from a Schedule I drug to a Schedule II drug.[93] News reports noted that this reclassification makes Oregon the 'first state in the nation to make marijuana anything less serious than a Schedule I drug.'[94]

Washington[edit]

Dea Drug Schedule List Chart

On Nov. 6, 2012: After passing Initiative 502, Washington is one of the first two states to legalize the recreational use of marijuana for individuals over the age of 21.[95]

Wisconsin[edit]

Gary Storck sent a letter to the Controlled Substances board in August 2011 requesting procedures to file a petition, which is discussed at the September 2011 Controlled Substances Board Meeting.[96]The Wisconsin Controlled Substances board has authority to reschedule cannabis pursuant to the rule-making procedures of ch. 227.[97]Drafters plan to submit a petition to the Controlled Substances Board in early 2012.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^DEA 51 FR 17476-78.

- ^David Savage (October 16, 2012). 'Medical marijuana advocates seek reclassification of drug'. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2012-10-27.

- ^Americans for Safe Access v. DEA (DC Cir. 2013). Text

- ^'28 Legal Medical Marijuana States and DC - Medical Marijuana - ProCon.org'.

- ^Edney, Anna (June 20, 2014). 'Marijuana Considered for Looser Restrictions by U.S. FDA'. Bloomberg.

- ^Bernstein, Lenny (August 11, 2016). 'U.S. affirms its prohibition on medical marijuana'. Washington Post.

- ^Halper, Evan (August 11, 2016). 'DEA ends its monopoly on marijuana growing for medical research'. LA Times.

- ^Miron, Jeffrey A., Waldock, Katherine. (2010). 'The Budgetary Impact of Ending Drug Prohibition'. Cato Institute. For the original paper, see Miron, Jeffrey A. (2005). 'The Budgetary Implications of Drug Prohibition'. Marijuana Policy Project; See also Caputo, M. R., & Ostrom, B.J. (1994). 'Potential tax revenue from a regulated marijuana market: A meaningful revenue source'. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 53, 475–490.

- ^Aggarwal, Sunil (2010). 'Cannabis: A Commonwealth Medicinal Plant, Long Suppressed, Now at Risk of Monopolization'(PDF). Denver University Law Review. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- ^ abcJon Gettman (May 13, 1999). 'Science And The End Of Marijuana Prohibition'(PDF). drugrehaballiance.com. Retrieved 2014-12-12. Text originally presented at the 12th International Conference on Drug Policy Reform.

- ^Accepted Medical Use of Cannabis: State Laws.The 2002 Petition to Reschedule Cannabis (Marijuana). DrugScience.org. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ^'Active State Medical Marijuana Programs'. NORML. December 1, 2004. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^Accepted Medical Use: Medical Professionals.The 2002 Petition to Reschedule Cannabis (Marijuana). DrugScience.org. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ^Accepted Medical Use: Route of Administration.The 2002 Petition to Reschedule Cannabis (Marijuana). DrugScience.org. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ^Herkenham M, Lynn A, Little M, Johnson M, Melvin L, de Costa B, Rice K (1990). 'Cannabinoid receptor localization in brain'. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.87 (5): 1932–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.5.1932. PMC53598. PMID2308954.Free full text

- ^ abcJon Gettman (July 11, 1997). 'Dopamine and the Dependence Liability of Marijuana'. UK Cannabis Internet Activists. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. 'United States Patent, Cannabinoids as Antioxidants and Neuroprotectants'. United States Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- ^American College of Physicians (January 2008). 'Supporting Research into the Therapeutic Role of Marijuana'. Archived from the original on 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ^'The future of federal marijuana laws'. The Green Pulpit. Archived from the original on 2014-12-22.

- ^U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. 'DEA History Book, 1990–1994. Medical Use of Marijuana Denied (1992)'. United States Department of Justice. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^ abcdeDonnie R. Marshall (March 28, 2001). 'Notice of Denial of Petition'. In: Office of the Federal Register (April 18, 2001). 66 F.R. 20037. Government Printing Office. Retrieved on 2007-04-28.

- ^Pub.L.106–172. Retrieved on 2007-04-29.

- ^U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (March 13, 2000). 'GHB added to the list of schedule i controlled substances' (Press release). United States Department of Justice. Archived from the original on April 7, 2007. Retrieved April 28, 2007.

- ^H.R. 2306, The Ending Federal Marijuana Prohibition Act 2011

- ^ ab21 U.S.C.§ 811. Retrieved on 2007-04-28 from Cornell Law School's Legal Information Institute.

- ^Statement on 'Date Rape' Drugs by Nicholas Reuter, M.P.H.Archived 2006-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, Associate Director for Domestic and International Drug Control, Office of Health Affairs, Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Testimony before the House Committee on Commerce, Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, March 11, 1999.

- ^21 U.S.C.§ 811d. Retrieved on 2007-04-28 from Cornell Law School's Legal Information Institute.

- ^'Report of the [Canadian] Senate Special Committee on Illegal Drugs'. Drugtext.org. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- ^ ab'Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961'(PDF). Archived from the original(PDF) on 2008-05-09.(502 KB). United NationsInternational Narcotics Control Board. Retrieved on 2007-04-28. Amended in 1972; schedules revised on March 5, 1990. Also available directly from Wikisource in HTML format.

- ^ abSingle Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961. Article 2. Also available directly from Wikisource in HTML format.

- ^Neier, Aryeh (March 5, 2005). 'U.S. ideologues put millions at risk'. International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2007-04-28.Op-ed piece.

- ^Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961. Article 46. Also available directly from Wikisource in HTML format.

- ^Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961. Article 47. Also available directly from Wikisource in HTML format.

- ^Fazey, Cindy (April 2003). 'The UN Drug Policies and the Prospect for Change'. Fuoriluogo.it. Forum Droghe. Archived from the original on 2015-04-23. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^1998 Congressional Record, Vol. 144, Page H7719 through H7726 (PDF). Retrieved on 2007-04-28.

- ^'Rep. Barney Frank Re-Introduces Medicinal Marijuana Bill Previously Co-Sponsored by Rep. Newt Gingrich' (Press release). Marijuana Policy Project. November 13, 1995. Archived from the original on February 7, 2005. Retrieved on 2007-04-28 through Archive.org.

- ^Kuipers, Dean (June 25, 2003). 'Burnt: Medical use of marijuana has been legal in California since 1996'. Americans for Safe Access. Archived from the original on June 6, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^Jon Gettman. The Distinction Between Marinol, Dronabinol, and Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). The Bulletin of Cannabis Reform. DrugScience.org. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- ^Carl Olsen. Sacramental Cannabis Lawsuit Challenges Marijuana Prohibition On Establishment and Free Exercise of Religion. The Bulletin of Cannabis Reform. DrugScience.org. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- ^Young, Francis L. (September 6, 1988). 'In The Matter Of MARIJUANA RESCHEDULING PETITION, Docket No. 86-22: OPINION AND RECOMMENDED RULING, FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND DECISION OF ADMINISTRATIVE LAW JUDGE'. Schaffer Library of Drug Policy. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^Doblin, Rick (1994). 'The Medicinal Use Of Marijuana - A Progress Report On Dr. Donald Abrams' Pilot Study Comparing Smoked Marijuana And The Oral THC Capsule For The Promotion Of Weight Gain In Patients Suffering from the AIDS Wasting Syndrome'. Newsletter of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. 5 (1). Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^'Medicinal marijuana: the struggle for legalization'. CNN. 1997. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^Herkenham M (1992). 'Cannabinoid receptor localization in brain: relationship to motor and reward systems'. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 654: 19–32. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb25953.x. PMID1385932.

- ^'NIDA for Teens: Facts on Drugs – Marijuana'. U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse. June 10, 2005. Archived from the original on April 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^Janet E. Joy, Stanley J. Watson, Jr., and John A. Benson, Jr., editors; Division of Neuroscience and Behavioral Health, Institute of Medicine (1999). Marijuana and medicine: assessing the science base. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. ISBN0-309-07155-0.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)Free full text

- ^U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. 'Exposing the Myth of Smoked Medical Marijuana'. United States Department of Justice. Archived from the original on April 17, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^Gieringer, Dale (1996). 'Marijuana Water Pipe and Vaporizer Study'. Newsletter of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. 6 (3). Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^Jon Gettman (July 27, 1999). 'Jon Gettman Comments On The Rescheduling of Marinol'. MarijuanaNews.com. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^'Federal Register, Volume 66 Issue 75 (Wednesday, April 18, 2001)'.

- ^'Arguments Supporting the Cannabis Rescheduling Petition'. The 2002 Petition to Reschedule Cannabis (Marijuana). DrugScience.org. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^'NATIONAL COALITION SEEKS RECOGNITION OF THE ACCEPTED MEDICAL USE OF CANNABIS IN THE UNITED STATES; Petition Provides Scientific Argument For Rescheduling' (Press release). Coalition for Rescheduling Cannabis. October 9, 2002. Retrieved 2007-04-28. Text of petition available at 'The Cannabis Rescheduling Petition: An Introduction'. The 2002 Petition to Reschedule Cannabis (Marijuana). DrugScience.org. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^Mauro, Tony (June 6, 2005). 'High Court: Federal Drug Laws Can Trump State Medical Marijuana Laws'. Legal Times.

- ^Coalition to Reschedule Cannabis (May 23, 2011). 'Petition for writ of mandamus to the drug enforcement administration and the united states attorney general'(PDF). cannabisnews.com. Archived from the original(PDF) on June 26, 2011. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^'Final Determination on the Petition for Rescheduling'(PDF). DEA. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2013-07-08.

- ^Petitioner's Reply in Support of Petition for Writ of Mandamus, In re Coal. to Reschedule Cannabis (11-5121), 2011 WL 3382393 (C.A.D.C. Aug. 4, 2011).

- ^In Re: Coal. to Reschedule Cannabis, et al., No. 11-5121 (C.A.D.C. Oct. 14, 2011)(unpublished [pursuant to D.C. Cir. Rule 36]).

- ^Americans for Safe Access (January 23, 2012). 'Patient Advocates File Appeal Brief in Federal Case to Reclassify Medical Marijuana'. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ^Americans for Safe Access (August 1, 2012). 'Medical Marijuana Case On Therapeutic Value, Rescheduling To Be Heard In Federal Court'. Huffington Post. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ^U.S. Court of Appeal for the District of Columbia Circuit (October 16, 2012). 'Order for Supplemental Briefing'(PDF). Archived from the original(PDF) on October 30, 2012.

- ^Americans for Safe Access (October 22, 2012). 'Petitioners' Supplemental Brief on Standing'(PDF). Archived from the original(PDF) on November 19, 2012.

- ^Office of the Governor of Washington (2011-11-30). 'Gov. Gregoire files petition to reclassify marijuana'.[permanent dead link]

- ^Offices of the Governors of the States of Washington and Rhode Island (2011-11-30). 'Petition to DEA'(PDF). Archived from the original(PDF) on 2012-09-16.

- ^'FDA issues marijuana rescheduling recommendation to DEA'. Marijuana.com.

- ^ ab'H.R.2306 - Ending Federal Marijuana Prohibition Act of 2011'. congress.gov. Retrieved 2017-02-22.

- ^ ab'H.R.6606 - Respect States' and Citizens' Rights Act of 2012'. congress.gov. Retrieved 2017-02-22.

- ^'H.R. 6606 (112th): Respect States' and Citizens' Rights Act of 2012'. govtrack. Retrieved 2017-02-22.

- ^ ab'H.R.1013 - Regulate Marijuana Like Alcohol Act'. congress.gov. Retrieved 2017-02-22.

- ^'U.S. affirms its prohibition on medical marijuana'. The Washington Post. 11 August 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^2016 Democratic Party PlatformArchived 2016-11-10 at the Wayback Machine (July 21, 2016), as Approved by the Democratic Platform Committee, July 8–9, 2016, Orlando, FL, page 16.

- ^David Weigel, Democrats call for 'pathway' to marijuana legalization, The Washington Post (July 9, 2016).

- ^Hearings, Briefings, Meetings, National Institute on Drug Abuse Congressional Affairs Dept., February 10, 2017

- ^Tom Jackman (April 30, 2014), 'Va. Rep. Griffith introduces federal 'Legitimate Use of Medicinal Marijuana Act'', The Washington Post

- ^Andrew Blake (April 8, 2017), 'Bipartisan bill would reclassify marijuana as Schedule 3 substance', The Washington Times

- ^Alicia Wallace (April 6, 2017), 'New federal bill would reschedule marijuana as Schedule III', The Cannabist, The Denver Post

- ^Patricia Kime (September 8, 2016), 'American Legion throws weight behind marijuana research', Military Times

- ^Bruce Kennedy (May 22, 2017), 'American Legion calls on Trump to take cannabis off Schedule I to help vets', The Cannabist, The Denver Post

- ^Bryan Bender (May 20, 2017), American Legion to Trump: Allow marijuana research for vets – Under current rules, doctors with the Department of Veterans Affairs cannot even discuss marijuana as an option with patients, Politico

- ^Alex Pasquariello (July 25, 2017), 'Federal lawsuit against Sessions and DEA says marijuana's Schedule I status unconstitutional', The Cannabist, The Denver Post

- ^Alex Pasquariello (February 26, 2018), 'Lawsuit challenging Sessions and DEA on marijuana's Schedule I status dismissed by federal judge', The Cannabist, The Denver Post

- ^Teaganne Finn, Erik Wasson, and Daniel Flatley (November 29, 2018), Lawmakers Reach Farm Bill Deal by Dumping GOP Food-Stamp Rules, Bloomberg,

The bill includes a provision that would make hemp a legal agricultural commodity after Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky championed the proposal, even joining the farm bill conference committee to ensure it would be incorporated. Among other changes to existing law, hemp will be removed from the federal list of controlled substances and hemp farmers will be able to apply for crop insurance.

CS1 maint: Uses authors parameter (link) - ^Adam Drury (November 30, 2018), 'Industrial Hemp is Now Included in the 2018 Farm Bill', High Times,

This year's Farm Bill, however, goes much further, changing federal law on industrial and commercial hemp and, remarkably, introducing the first-ever changes to the Controlled Substances Act of 1970.

- ^'Reconciled Farm Bill Includes Provisions Lifting Federal Hemp Ban', Legislative blog, NORML, November 29, 2018,

The [bill] for the first time amends the federal Controlled Substances Act of 1970 so that industrial hemp plants containing no more than 0.3 percent THC are no longer classified as a schedule I controlled substance. (See page 1182, Section 12608: 'Conforming changes to controlled substances act.') Certain cannabinoid compounds extracted from the hemp plant would also be exempt from the CSA.

- ^Ferner, Matt (November 6, 2012). 'Denver Editor for the Huffington Post'. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^Nohlgren, Stephen (January 28, 2014). 'Questions and answers about medical marijuana in Florida'. Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^Ferner, Matt (11 June 2014). 'Sheldon Adelson Funds Florida Anti-Medical Marijuana Campaign'. Huffington Post. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^url='Archived copy'. Archived from the original on 2015-01-13. Retrieved 2015-01-12.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- ^https://www.leafly.com/news/politics/states-and-countries-with-the-biggest-cannabis-wins-in-2016

- ^'Iowa Board of Pharmacy recommends rescheduling marijuana'. The Northern Iowan. 2010-02-22. Archived from the original on 2012-03-30.

- ^'Rescheduling Petition 3/16/11'. Archived from the original on 2012-08-18. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^'Rescheduling Memorandum 3/16/11'. Archived from the original on 2012-09-18. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ^'HF 57 Conference Committee Report - 87th Legislature (2011 - 2012)'.

- ^'Journal of the House 2011 Supplement'.

- ^Dworkin, Andy (2010-06-20). 'Recognizing medical marijuana, state pharmacy board changes its legal classification'. The Oregonian. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- ^KVAL News (2010-06-17). 'Oregon Board of Pharmacy vote a marijuana milestone'. KATU. Archived from the original on 2010-06-23. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- ^Sledge, Matt (November 7, 2012). 'reporter for the Huffington Post'. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^WI Department of Regulation and Licensing (2011-09-03). 'Wisconsin Controlled Substances Board meeting agenda September 8, 2011'.

- ^State of Wisconsin (2011-09-03). 'Wisconsin Statutes'.

Further reading[edit]

- Basis for the Recommendation for Maintaining Marijuana in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, 20037–20076, Department of Health and Human Services, Volume 66, Number 75, Federal Register, 18 April 2001. Retrieved on 2007-04-28

- Coalition Files Federal Administrative Petition To Legalize Medical Marijuana, NORML News, 10 October 2002. Retrieved on 2007-04-28

- Drugs of Abuse: Chapter 1, The Controlled Substances Act, Drug Enforcement Administration, 2005. Retrieved on 2007-04-28

- Gettman v. DEA Government Response, The Rescheduling of Marijuana Under Federal Law Government's Reply Brief, 14 January 2002. Retrieved on 2007-04-28

- Gieringer D.: The Acceptance of Medicinal Marijuana in the U.S., J Cannabis Ther 2002;3(1): in press.

- High Court in Washington DC & the DEA Upholds Marijuana as Dangerous Drug United States Court of Appeals in Washington DC Upholds Marijuana as a Dangerous Drug. Retrieved on 2016-11-16

External links[edit]

Federal government:

Advocacy groups:

The drug has a potential for abuse less than the drugs in schedules 1 and 2. The drug has a currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States. Abuse of the drug may lead to moderate or low physical dependence or high psychological dependence.

The following drugs are listed as Schedule 3 (III) Drugs* by the Controlled Substances Act (CSA):

The Controlled Substances Act (CSA) schedule information displayed applies to substances regulated under federal law. There may be variations in CSA schedules between individual states.

| Drug Name ( View by: Brand Generic ) |

|---|

| Adipost (More..) generic name: phendimetrazine |

| Anabolin LA (More..) generic name: nandrolone |

| Anadrol-50(Pro, More..) generic name: oxymetholone |

| Andro LA 200 (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Andro-Cyp 100 (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Andro-Cyp 200 (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Androderm(Pro, More..) generic name: testosterone |

| AndroGel(Pro, More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Android(Pro, More..) generic name: methyltestosterone |

| Android-10 (More..) generic name: methyltestosterone |

| Android-25 (More..) generic name: methyltestosterone |

| Androlone-D (More..) generic name: nandrolone |

| Androxy(Pro, More..) generic name: fluoxymesterone |

| Andryl 200 (More..) generic name: nandrolone |

| Anorex-SR (More..) generic name: phendimetrazine |

| Appecon (More..) generic name: phendimetrazine |

| Ascomp with Codeine(Pro, More..) generic name: aspirin/butalbital/caffeine/codeine |

| Aveed(Pro, More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Axiron(Pro, More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Belbuca(Pro, More..) generic name: buprenorphine |

| Bontril PDM(More..) generic name: phendimetrazine |

| Bontril Slow Release(Pro, More..) generic name: phendimetrazine |

| Bunavail(More..) generic name: buprenorphine/naloxone |

| Buprenex(Pro, More..) generic name: buprenorphine |

| Busodium (More..) generic name: butabarbital |

| Butalbital Compound(More..) generic name: aspirin/butalbital/caffeine |

| Butisol Sodium(More..) generic name: butabarbital |

| Butrans(Pro, More..) generic name: buprenorphine |

| Cassipa(More..) generic name: buprenorphine/naloxone |

| Coldcough Syrup (Pro, More..) generic name: chlorpheniramine/dihydrocodeine/pseudoephedrine |

| Colrex (More..) generic name: acetaminophen/chlorpheniramine/codeine/phenylephrine |

| Colrex Compound (More..) generic name: acetaminophen/chlorpheniramine/codeine/phenylephrine |

| Cotabflu (More..) generic name: acetaminophen/chlorpheniramine/codeine |

| Covaryx(Pro, More..) generic name: esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone |

| Covaryx HS(More..) generic name: esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone |

| Deca-Durabolin (More..) generic name: nandrolone |

| Delatest (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Delatestadiol (More..) generic name: estradiol/testosterone |

| Delatestryl(Pro, More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Dep Androgyn (More..) generic name: estradiol/testosterone |

| Depandro 100 (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Depo-Testadiol (More..) generic name: estradiol/testosterone |

| Depo-Testosterone(Pro, More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Depotest (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Depotestogen (More..) generic name: estradiol/testosterone |

| DHC Plus (More..) generic name: acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine |

| Didrex(Pro, More..) generic name: benzphetamine |

| Dihydro-CP (Pro, More..) generic name: chlorpheniramine/dihydrocodeine/pseudoephedrine |

| DiHydro-GP (More..) generic name: dihydrocodeine/guaifenesin/pseudoephedrine |

| Donatuss DC (Pro, More..) generic name: dihydrocodeine/guaifenesin/phenylephrine |

| Duo-Cyp (More..) generic name: estradiol/testosterone |

| Dura-Dumone (More..) generic name: estradiol/testosterone |

| Durabolin (More..) generic name: nandrolone |

| Durabolin 50 (More..) generic name: nandrolone |

| Duratest (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Duratestrin (More..) generic name: estradiol/testosterone |

| Durathate 200 (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Dvorah(Pro, More..) generic name: acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine |

| EEMT(Pro, More..) generic name: esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone |

| EEMT DS(More..) generic name: esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone |

| EEMT HS(More..) generic name: esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone |

| Empirin with Codeine (More..) generic name: aspirin/codeine |

| Essian(More..) generic name: esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone |

| Essian H.S.(More..) generic name: esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone |

| Estra-Testrin (More..) generic name: estradiol/testosterone |

| Estratest(More..) generic name: esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone |

| Estratest H.S.(More..) generic name: esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone |

| Everone (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Farbital (More..) generic name: aspirin/butalbital/caffeine |

| Fioricet with Codeine(Pro, More..) generic name: acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/codeine |

| Fiorinal(Pro, More..) generic name: aspirin/butalbital/caffeine |

| Fiorinal with Codeine(Pro, More..) generic name: aspirin/butalbital/caffeine/codeine |

| Fiorinal with Codeine III(More..) generic name: aspirin/butalbital/caffeine/codeine |

| Fiormor (More..) generic name: aspirin/butalbital/caffeine |

| Fiortal (More..) generic name: aspirin/butalbital/caffeine |

| Fiortal with Codeine (More..) generic name: aspirin/butalbital/caffeine/codeine |

| FIRST-Testosterone(More..) generic name: testosterone |

| FIRST-Testosterone MC (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Fortabs (More..) generic name: aspirin/butalbital/caffeine |

| Fortesta(Pro, More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Fycompa(Pro, More..) generic name: perampanel |

| Giltuss Ped-C (More..) generic name: codeine/guaifenesin/phenylephrine |

| Halotestin (Pro, More..) generic name: fluoxymesterone |

| Histerone (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Hybolin Decanoate (More..) generic name: nandrolone |

| Hybolin-Improved (More..) generic name: nandrolone |

| Hydro-Tussin DHC (More..) generic name: chlorpheniramine/dihydrocodeine/pseudoephedrine |

| Hydro-Tussin EXP (More..) generic name: dihydrocodeine/guaifenesin/pseudoephedrine |

| Idenal (More..) generic name: aspirin/butalbital/caffeine |

| J-Cof DHC (Pro, More..) generic name: brompheniramine/dihydrocodeine/pseudoephedrine |

| J-Max DHC (Pro, More..) generic name: dihydrocodeine/guaifenesin |

| Jatenzo (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Ketalar(Pro, More..) generic name: ketamine |

| Laniroif (More..) generic name: aspirin/butalbital/caffeine |

| LidoProfen (More..) generic name: ketamine/ketoprofen/lidocaine topical |

| Maxiflu CD (More..) generic name: acetaminophen/codeine/guaifenesin/pseudoephedrine |

| Maxiflu CDX (More..) generic name: acetaminophen/codeine/guaifenesin/pseudoephedrine |

| Maxiphen CD (More..) generic name: codeine/guaifenesin/phenylephrine |

| Maxiphen CDX (More..) generic name: codeine/guaifenesin/phenylephrine |

| Meditest (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Melfiat(More..) generic name: phendimetrazine |

| Menogen(More..) generic name: esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone |

| Menogen HS (More..) generic name: esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone |

| Methitest(Pro, More..) generic name: methyltestosterone |

| MKO Melt Dose Pack (More..) generic name: ketamine/midazolam/ondansetron |

| MKO Troche (More..) generic name: ketamine/midazolam/ondansetron |

| Natesto(Pro, More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Obezine(More..) generic name: phendimetrazine |

| Oreton Methyl (More..) generic name: methyltestosterone |

| Oxandrin(Pro, More..) generic name: oxandrolone |

| Pancof (More..) generic name: chlorpheniramine/dihydrocodeine/pseudoephedrine |

| Pancof EXP (More..) generic name: dihydrocodeine/guaifenesin/pseudoephedrine |

| Panlor(Pro, More..) generic name: acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine |

| Panlor DC(More..) generic name: acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine |

| Panlor SS(More..) generic name: acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine |

| Pentothal (Pro, More..) generic name: thiopental |

| Phendiet(More..) generic name: phendimetrazine |

| Phendiet-105(More..) generic name: phendimetrazine |

| Phenflu CD (More..) generic name: acetaminophen/codeine/guaifenesin/phenylephrine |

| Phenflu CDX (More..) generic name: acetaminophen/codeine/guaifenesin/phenylephrine |

| Phrenilin with Caffeine and Codeine(Pro, More..) generic name: acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/codeine |

| Plegine (More..) generic name: phendimetrazine |

| Poly Hist DHC (Pro, More..) generic name: dihydrocodeine/phenylephrine/pyrilamine |

| Poly Tussin EX (More..) generic name: dihydrocodeine/guaifenesin/phenylephrine |

| Poly-Tussin EX Syrup (Pro, More..) generic name: dihydrocodeine/guaifenesin/phenylephrine |

| Prelu-2(More..) generic name: phendimetrazine |

| Prelu-2 TR (More..) generic name: phendimetrazine |

| Probuphine(Pro, More..) generic name: buprenorphine |

| Recede (Pro, More..) generic name: benzphetamine |

| Regimex(Pro, More..) generic name: benzphetamine |

| Soma Compound with Codeine (Pro, More..) generic name: aspirin/carisoprodol/codeine |

| Spravato(Pro, More..) generic name: esketamine |

| Statobex (More..) generic name: phendimetrazine |

| Striant(Pro, More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Sublocade(Pro, More..) generic name: buprenorphine |

| Suboxone(Pro, More..) generic name: buprenorphine/naloxone |

| Subutex(More..) generic name: buprenorphine |

| Synalgos-DC(Pro, More..) generic name: aspirin/caffeine/dihydrocodeine |

| Syntest DS (More..) generic name: esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone |

| Syntest HS (More..) generic name: esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone |

| Teslac(Pro, More..) generic name: testolactone |

| Testamone-100 (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Testim(Pro, More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Testo-100 (Pro, More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Testoderm (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Testolin (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Testopel (Pro, More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Testopel Pellets(More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Testred(Pro, More..) generic name: methyltestosterone |

| Testro (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Testro AQ(More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Testro-LA (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Trezix(Pro, More..) generic name: acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine |

| Tricof (More..) generic name: chlorpheniramine/dihydrocodeine/pseudoephedrine |

| Tridal (More..) generic name: codeine/guaifenesin/phenylephrine |

| Uni-Cof (More..) generic name: chlorpheniramine/dihydrocodeine/pseudoephedrine |

| Uni-Cof Expectorant (More..) generic name: dihydrocodeine/guaifenesin/pseudoephedrine |

| Valertest No 1 (More..) generic name: estradiol/testosterone |

| Virilon (More..) generic name: methyltestosterone |

| Virilon IM (More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Vogelxo(Pro, More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Welltuss EXP (More..) generic name: dihydrocodeine/guaifenesin/pseudoephedrine |

| Winstrol (More..) generic name: stanozolol |

| Xyosted(Pro, More..) generic name: testosterone |

| Xyrem(Pro, More..) generic name: sodium oxybate |

| Zerlor(More..) generic name: acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine |

| Zubsolv(Pro, More..) generic name: buprenorphine/naloxone |